LONDON, Dec. 26, 2008 -- A man and his sketchbook.

LONDON, Dec. 26, 2008 -- A man and his sketchbook.Not something that is going to change the world.

Perhaps that is what Owen Jones thought as he set out in 1831 for four years of travel in Italy, Spain, Greece, Turkey, and Egypt.

After all he was just 22 and lots of young well-bred Englishmen his age were out doing the Grand Tour, with their notebooks or watercolors in hand.

Still, he had some ambitious plans. After six years of apprenticing as an architect, he wanted to earn fame of his own. So, he set out to make the first complete survey of the Alhambra -- the Moorish citadel that overlooks Granada and dates to the 14th century.

Along with a French colleague, Jules Goury, Jones spent months making meticulous drawings of the palace's ornamental details, along with detailed plans of the buildings. Then in the middle of the project Goury died of cholera.

At that point, Jones might have stopped because the job was already more than enough work for two people. But he continued alone and in the process discovered his lifelong passion: cataloging mankind's vast variety of design traditions.

The Alhambra drawings were published in London in 1845 and helped spark a wave of new interest in Eastern design among Jones' fellow architects, commercial artists and interior designers.

By then Jones was already busy on what would become his masterwork: a global survey of architectural ornamentation drawn from the rest of his travel sketches and exhaustive library research.

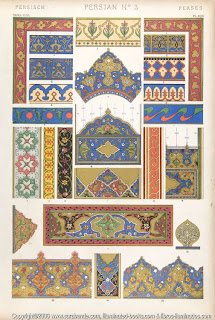

His masterwork, The Grammar of Ornament published in 1856, included some 100 full-color plates of designs ranging from Greek, to Roman, to Byzantine, to Moorish, to Egyptian, to Persian, to Indian to Chinese.

His masterwork, The Grammar of Ornament published in 1856, included some 100 full-color plates of designs ranging from Greek, to Roman, to Byzantine, to Moorish, to Egyptian, to Persian, to Indian to Chinese. This plate is one of the many presenting Persian designs.

Jones even included the incised patterns on wooden weapons from the Pacific islands, making his plates easily the most extensive and influential design catalog produced up to his time.

The Grammar was partly so successful because it both caught and advanced the spirit of Jones' own rapidly changing world. It came out just as Britain and other colonial powers were becoming fascinated by the vast variety of lands they ruled and Europeans were hungry for more information about them.

That fascination was perfectly embodied by the fad of Orientalism that created a market for everything from travel literature, to exotic paintings, to archaeological excavations.

This Orientalist painting by Frederic Lewis in 1857, entitled Harem Life in Constantinople, is typical of the genre.

This Orientalist painting by Frederic Lewis in 1857, entitled Harem Life in Constantinople, is typical of the genre.But if Jones' catalog provided a sourcebook of world designs that greatly interested other Western architects and craftsmen, his contemporaries did not always use his reference work as he intended.

Along with the images, the Grammar included Jones' personal guidelines for the proper use of ornamentation in artwork.

One of his propositions was that "the first principle of architecture is to decorate construction, never to construct decoration." Another was that the purpose of all design is to create a sense of repose through proportion and harmony.

But most Victorian-age commercial designers thought just the opposite. They took the most effusive designs in the Grammar' and copied them wholesale as wallpaper, curtains, and furniture covers.

The result was that -- instead of the Eastern designs being integrated into Western ones -- the Victorian era's famously overstuffed parlors became even more wildly overdecorated and disharmonious than before.

Still, Jones did eventually get the chance to try to turn some of his maxims into reality. As a prominent architect and interior decorator, he was named superintendent of works for Britain's Great Exhibition of 1851.

The Exhibition was the first World Fair and its centerpiece was the Crystal Palace, a huge iron-and-glass building designed in a vaguely Moorish style. It was filled with artifacts and replicas of artworks from around the world and visitors mobbed it daily.

The Exhibition was the first World Fair and its centerpiece was the Crystal Palace, a huge iron-and-glass building designed in a vaguely Moorish style. It was filled with artifacts and replicas of artworks from around the world and visitors mobbed it daily. The six-month exhibition was a huge success. By the time it closed, some 6 million people visited -- equivalent to about half of Britain's population at the time.

And the exotic Moorish design of the Crystal Palace proved such a crowd pleaser that its life did not end with the fair. Instead, it was moved to a permanent London site where it remained as an exhibition hall until it was destroyed by a fire in 1936.

The Crystal Palace probably had a more direct impact on Western architecture than did Jones' Grammar. That is because it helped inspire the construction of a whole string of other vaguely Eastern-looking buildings as entertainment centers.

Shown here is the Regal Theater in Chicago, which originally opened as the Avalon Theater in 1927. Other famous "Eastern" playgrounds include Grauman's Chinese Theater, which has been a Hollywood landmark since 1927.

Shown here is the Regal Theater in Chicago, which originally opened as the Avalon Theater in 1927. Other famous "Eastern" playgrounds include Grauman's Chinese Theater, which has been a Hollywood landmark since 1927.But in a strange twist of East meets West, the sudden enthusiasm for Eastern styles never spread beyond theaters and music halls.

The reason seems to be that Victorians could associate Eastern designs with pleasure palaces but could never reconcile them with normal workaday life.

Terry Reece Hackford observes in a 1981 thesis for Brown University that Moorish design commonly held "pleasurable and often erotic associations" for the Victorian public in the 1850s and 60s and this quality of association "limited the context in which an Eastern style was appropriate."

Does that mean that Owen Jones was ultimately wrong in thinking Eastern motifs could become a major source of inspiration for Western architects and interior designers?

The answer is both yes and no.

It is true that Eastern designs have had little impact on the way Western homes are constructed, despite some appealing possibilities. Here, for example, is a rare use of Moorish arches to open up a dining room area.

It is true that Eastern designs have had little impact on the way Western homes are constructed, despite some appealing possibilities. Here, for example, is a rare use of Moorish arches to open up a dining room area.But Jones' catalog did become increasingly influential over time, and helped inject Eastern ornamentation into the Arts and Crafts Movement and, later, the Art Nouveau Movement. Both trends combined Eastern and other motifs to explore new looks in the decorative arts.

Today, the Grammar of Ornament remains very well known to professional designers. There is every reason to suspect that, as artists keep looking for new inspirations, Jones' sketchbook will keep producing surprises.

(The plate at the top of this article is of a window in the Alhambra, drawn by Jones and Goury.)

#

RETURN TO HOME

#

Related Links:

Wickipedia: Owen Jones, Architect

V&A Museum: The Alhambra

Terry Reece Hackford: The Great Exhibition and Moorish Architecture and Design in Great Britain

Owen Jones’ propositions concerning architecture and decorative arts

Plates from The Grammar of Ornament: Giornale Nuovo